Vivienne and Margot turn one this month. I have two one-year-olds. How the heck did that happen?

This is the story of how two babies and a hospital stole my heart.

The apex of a rollercoaster is that moment before the drop. It’s the moment where you may want to change your mind, but even if you do, you can’t change your circumstances. You can’t make it stop. The only thing within your control is how you respond, and even that feels involuntary.

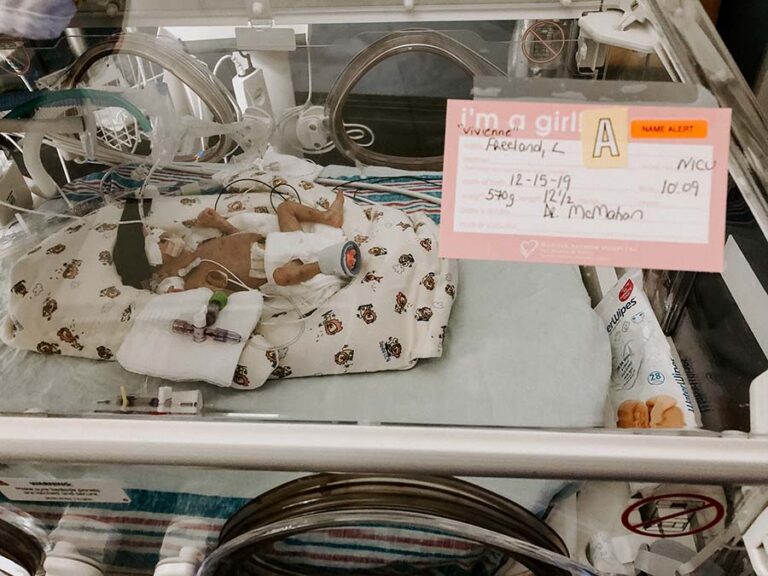

My apex was at 10 am on Sunday, December 15, 2019. I couldn’t feel the contractions, but I watched the lines rise and fall much closer together on the monitor. I felt a baby so low that she didn’t even feel like she was still inside me. I wished that I could change my mind. I wished I could have traveled back in time and never taken that trip to Nantucket or had that Diet Coke. I wished a million wishes, but I couldn’t change my circumstances. I looked at my mother–totally resigned— and said, “the babies are coming and they are going to die.”

I was 22 weeks and 5 days pregnant. Just 2 weeks and 5 days past the halfway point of pregnancy—not yet in the third trimester, and two weeks from the nationally recognized “age of viability.” I had been admitted to the hospital 17 hours prior, with what I thought were Braxton Hicks contractions. The sonographer’s and nurses’ faces during my ultrasound told me everything I needed to know: things were not ok.

I came to in a hospital bed on the antepartum floor—a floor for patients whose only job is to stay pregnant. I took deep breaths and tried to distract myself from the intense cramping in my back and abdomen. In retrospect, I realize they sent me to the antepartum floor because I was barely dilated and my water wasn’t broken. There was still a chance that the girls would take their magnesium and stay put for another four months.

I don’t remember how they got there or how if they introduced themselves, I just remember them sitting at the foot of the bed telling me my babies would likely be sick and brain-damaged if they even survived. My interpretation is far crasser than what was said, I’m sure. They left the room and my husband and I were left to decide whether we would give our babies a fighting chance or let them go peacefully. And in a moment of intense, unmedicated pain, I said no. I didn’t want them to suffer because of my selfishness. We were supposed to sign something to make it official, but we never did. Instead, I begged for an epidural and was told it could only be administered on the labor and delivery floor.

“It doesn’t mean you’re having the babies,” the nurse explained, “it’s just where you have to go to get your epidural.”

“Ok. Take me there. I need an epidural.” After 6 hours of willing my unmedicated labor to stop, I was desperate for relief.

After the epidural, the contractions slowed. For ten hours I watched the monitor, relaxing when the line was flat; then anxious each time it rose. “It’s good that they are six minutes apart, right?” I asked the nurses over and over. They toed the line between polite and realistic with half-hearted smiles as they said, “maybe.”

At 10 am, the peaks and valleys on the monitor started to run much closer together. I went from feeling nothing at all to everything at once. It was the moment I told my mom the babies were going to die. I told the nurses to get a real doctor because a baby was coming. While I’m sure they made the call, there was a lack of urgency that—in retrospect—led me to believe they didn’t believe me. I can’t blame them. My water hadn’t broken, and I was only 3cm dilated, but I knew a baby was coming.

“I’m going to throw up, and the baby is going to come. Get a real doctor,” I pleaded.

My mom lifted the sheet. I heaved twice. With the first heave, my water broke. With the second, a baby came flying out of me and landed on the bed. My mom said she was trying to breathe. My husband said she was beautiful.

It seemed like only a few seconds before Dr. McMahan was standing at my bedside asking me, “what would you like me to do?” Vivienne’s medical records, however, say a nurse—who we’d later come to know as Tricia—was bagging the baby for several minutes before Dr. McMahan arrived.

Time stood still when he asked, “What would you like me to do?” And against everything I had so carefully considered the night before, I said, “you have to save her.”

“I’ll try.” He responded.

His face was serious, yet determined. Every time I read about a 22 weeker denied care, I think of these two words, and I wonder what if they had just tried?

What followed were the blurriest, longest, most desperate 51 hours of my life.